Murder-mutilation case in Laurel spawns book

LaReeca Rucker

The Oxford Eagle

A Laurel farmer stumbled upon a discarded package and discovered the mutilated remains of a woman inside.

That was Jan. 21, 1935, and the remains later were identified as Daisy Keeton. Authorities followed a trail of evidence that led to the interrogation, arrest and prosecution of her daughter, Ouida Keeton.

The comely killer is known today by some as "Mississippi's Lizzie Borden." And the controversial story involves murder, mutilation and prominent citizens.

Rankin County resident Hunter Cole has written a book, published by University Press of Mississippi, that tells the story.

"It's called The Legs Murder Scandal because all that was ever found of the murder victim were her legs," Cole said. "Ouida Keeton had disposed of the legs north of Laurel on a lonely trail the day after the murder."

They were found four hours later wrapped in sugar sacks, and police discovered evidence from the site at the Keeton home.

Ouida Keeton later implicated her former boss - and lover - W.M. Carter as the killer.

"When I heard about the publication of the book ... I was hoping my great-grandfather was treated fairly and respectfully," said Atlanta resident Ed R. Decker, Carter's great-grandson. "When I read it, I was satisfied that he was."

Cole, a Laurel native, was in the seventh-grade when he first heard about the case.

"My sister, who was in high school, mentioned that some students had been to Whitfield on a trip and had seen Ouida Keeton," Cole said, referring to the state mental hospital where Keeton wound up. "The story was very evocative. I wanted to learn more, but I had to wait until I was an old man," he said.

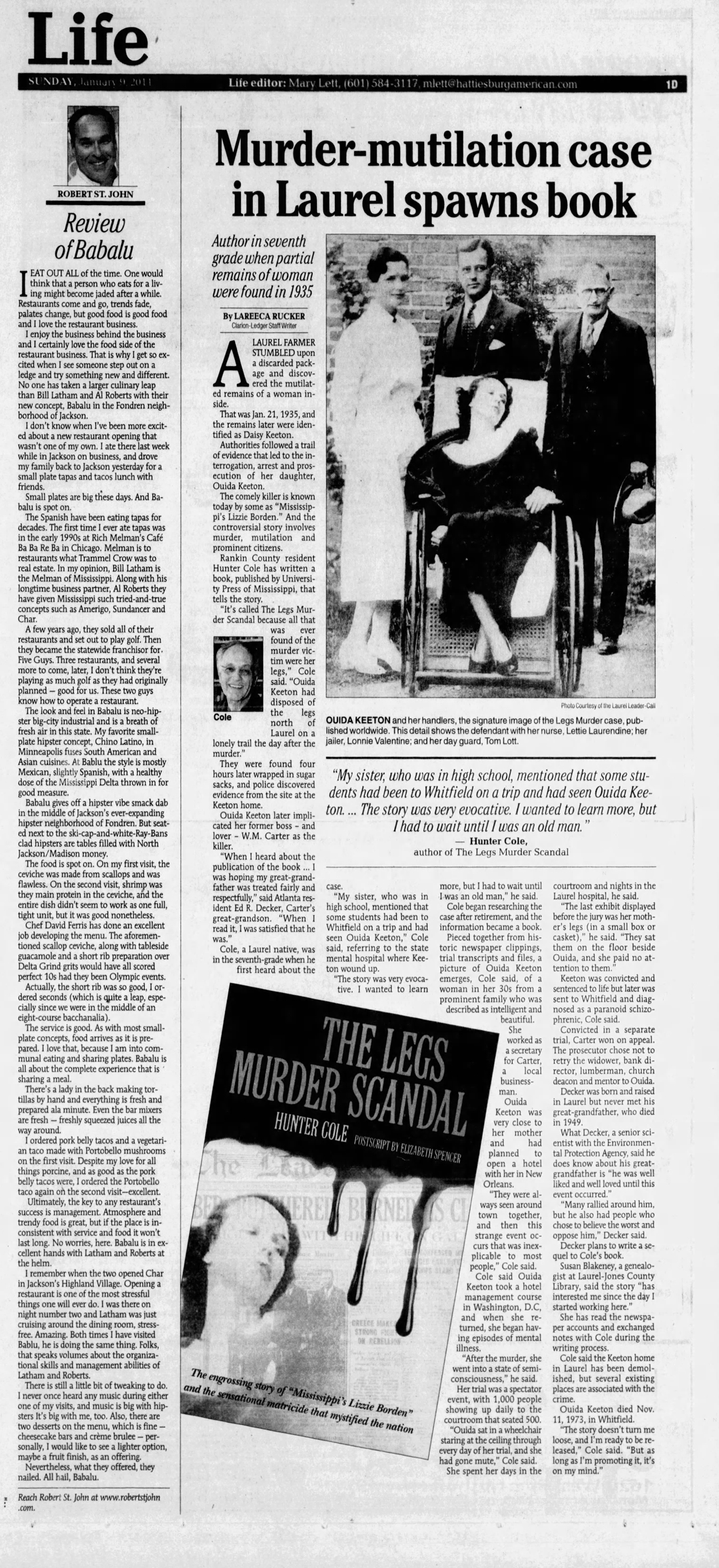

Cole began researching the case after retirement and the information became a book. Pieced together from historic newspaper clippings, trial transcripts and files, a picture of Ouida Keeton emerges, Cole said, of a woman in her 30s from a prominent family who was described as intelligent and beautiful. She worked as a secretary for Carter, a local businessman.

Ouida Keeton was very close to her mother and had planned to open a hotel with her in New Orleans.

"They were always seen around town together, and then this strange event occurs that was inexplicable to most people," Cole said.

Cole said Ouida Keeton took a hotel management course in Washington, D.C, and when she returned, she began having episodes of mental illness.

"After the murder, she went into a state of semi-consciousness," he said. Her trial was a spectator event, with 1,000 people showing up daily to the courtroom that seated 500. "Ouida sat in a wheelchair staring at the ceiling through every day of her trial, and she had gone mute," Cole said.

She spent her days in the courtroom and nights in the Laurel hospital, he said.

"The last exhibit displayed before the jury was her mother's legs (in a small box or casket)," he said. "They sat them on the floor beside Ouida, and she paid no attention to them."

Keeton was convicted and sentenced to life, but later was sent to Whitfield and diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic, Cole said.

Convicted in a separate trial, Carter won on appeal. The prosecutor chose not to retry the widower, bank director, lumberman, church deacon and mentor to Ouida.

Decker was born and raised in Laurel, but never met his great-grandfather, who died in 1949. What Decker, a senior scientist with the Environmental Protection Agency, said he does know about his great-grandfather is "he was well liked and well loved until this event occurred."

"Many rallied around him, but he also had people who chose to believe the worst and oppose him," said Decker, who plans to write a sequel to Cole's book.

Susan Blakeney, a genealogist at Laurel-Jones County Library, said the story "has interested me since the day I started working here." She has read the newspaper accounts and exchanged notes with Cole during the writing process.

Cole said the Keeton home in Laurel has been demolished, but several existing places are associated with the crime.

Ouida Keeton died Nov. 11, 1973, in Whitfield.

"The story doesn't turn me loose, and I'm ready to be released," Cole said. "But as long as I'm promoting it, it's on my mind."